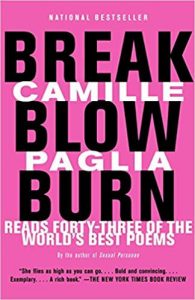

I’ve managed to spend some time with Camille Paglia’s Break, Blow, Burn in which she “reads” (i.e., explains) forty-three of the “world’s best poems.”

Hmm. Now I know the reading world can be roughly split up into two hemispheres: those who do poetry and those who don’t. I’m definitely one who does poetry. So it’s little surprise this book caught my eye (and that’s despite its blinding pink wrapper). I wondered about the forty-three poems she selected and why the odd number of just forty-three. As one who longs for numerological significance and symmetry, why not thirty-three? Or fifty?

You may be interested in:

Attempts at deciphering the reason for the odd number

I thought I’d find the answer in the Introduction, but no luck. I hate reading those under even the most ignorant of circumstances, and dare I say it, Paglia’s reads a bit like a cover letter that would do nicely atop an application package for an English faculty post at Brown. (As it happens, she’s a professor of humanities and media studies at the University of Arts in Philadelphia.)

I thought I’d find the answer in the Introduction, but no luck. I hate reading those under even the most ignorant of circumstances, and dare I say it, Paglia’s reads a bit like a cover letter that would do nicely atop an application package for an English faculty post at Brown. (As it happens, she’s a professor of humanities and media studies at the University of Arts in Philadelphia.)

Still, I forgive her, because the forty-three she chooses are spot on. If you care a lick about literature, you will recognise and come to love the ones she’s singled out as the top forty-three in the poetic hit parade of the English language, which makes this a book worth owning.

Among them are Shakespeare’s Sonnet 73, William Blake’s “London,” Wordsworth’s “The World Is Too Much With Us,” Yeats’s “The Second Coming” (probably my personal fave), William Carlos Williams’s “This Is Just to Say” (a genius work of free verse) and Wanda Coleman’s “Wanda Why Aren’t You Dead.”

Not exactly p-c in terms of gender or culture, but Paglia has her reasons, one being that she was working only with poetry written in English. The others I’ll leave you to read about in her intro.

Little contextual insights into the writers of these poems

While Paglia doesn’t exactly go out on a limb in her interpretations of these poems, her readings are clear and often insightful in terms of how form and content work together in poetry. She also offers interesting tidbits about the writers’ lives, like did you know that John Donne secretly married his lord’s wife’s niece, Anne More, in 1601 against just about everyone’s wishes?

The book gets its title, in fact, from part of Donne’s “Holy Sonnet XIV”:

“Batter my heart, three-person’d God; for you

As yet but knock, breathe, shine, and seek to mend;

Divorce me, untie, or break that knot again,

Take me to you, imprison me, for I

Except you enthral me, never shall be free,

Nor ever chaste, except you ravish me.”

Whew.

Paglia sticks to the traditionally religious reading of this poem. But I would argue it’s just as well applied to the contradictions inherent in any passion — the idea that you can’t get away from what you love and that one day you’ll beg to be ravished against your will.

And that’s the thing to remember about this book and about any decent piece of writing — it’s your own response that counts. Paglia’s offering a guide, and a very cogent one aimed at a lay audience. But these poems, like any literature that keeps hanging around the halls of time, operate on many many levels.

Break, Blow, Burn is available from Amazon.co.uk. A fine investment.

Elizabeth Frengel is a curator of rare books at The University of Chicago Library Book Arts and History