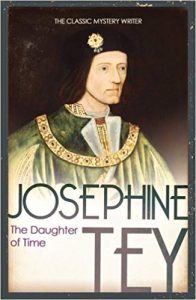

‘Truth is the daughter of time.'

That's the telling little epigram that opens Josephine Tey's  (the nom de plume of playwright Elizabeth MacKintosh) most intriguing, if not most popular, novel, The Daughter of Time. And history buffs, this one is for you.

(the nom de plume of playwright Elizabeth MacKintosh) most intriguing, if not most popular, novel, The Daughter of Time. And history buffs, this one is for you.

The book intrigues me because it's a mystery, but not one in the traditional sense. The story unfolds not in a stately manor house during the reading of a will, on the shadowy streets of Glasgow or on a luxury train speeding to the Orient. Rather this mystery unravels in the monastic cell of a hospital and almost exclusively in the mind of Inspector Alan Grant (a recurring hero in several of Tey's detective novels). What's more, the crime appears to have occurred some five hundred years earlier.

What is The Daughter of Time about?

Grant is flat on his back and on a painstakingly boring mend when a friend from the theatre brings him some prints as a sort of cheering up. One of those prints is a portrait of England's Richard III (b. 1452, d. 1485 at the Battle of Bosworth Field).

Grant figures he knows something about faces, but this one catches him up short. Suddenly Grant's on an obsessive endeavour to find out what made Richard III change from a loyal brother and honourable commander (and one of the richest and most powerful noblemen in England) to a child murderer and pretender to the throne. Problem is, Grant can't get up from his hospital bed.

I realise a premise like this promises to put to sleep all but the most earnest readers of British mysteries — but I'm telling you, The Daughter of Time is unputdownable. Perhaps it's because Grant is immobile and therefore reliant on his interactions with others. Or perhaps it's because the book is really a paper chase through history and the historical record.

Elizabeth Frengel is a curator of rare books at The University of Chicago Library Book Arts and History