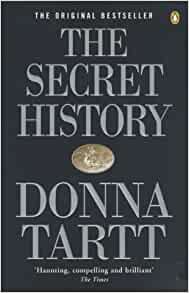

Hello, biblio-fans. Just a short blog this week because  I am technically still on vacation, or at least in vacation mode. You probably are, too. And I don't want to interrupt your reading, as this is prime snuggle-up-with-a-book time. Also, I'm only halfway through the book I'm about to blog: Donna Tartt's The Secret History, one of Alexandra's five favourite books of all time.

I am technically still on vacation, or at least in vacation mode. You probably are, too. And I don't want to interrupt your reading, as this is prime snuggle-up-with-a-book time. Also, I'm only halfway through the book I'm about to blog: Donna Tartt's The Secret History, one of Alexandra's five favourite books of all time.

It's not because The Secret History is without intrigue. There is plenty of that. In fact, the opener, reflecting on the scene of a murder, is one that would make Agatha Christie proud:

“The snow in the mountains was melting and Bunny had been dead for several weeks before we came to understand the gravity of our situation.”

The reason I'm only halfway through the book is that the exact nature of the grave situation the narrator, Richard Papen, finds himself in is unwound over a dense 559 pages. And I mean dense in terms of erudition, not dullness.

This is the mesmerizing story of a disaffected, lower-middle-class California boy who transfers to an ivied liberal arts university in the Northeast (based on Bennington, Alexandra tells me) and tries to reinvent himself. He hooks up with a very small, very quirky set who studies the classics exclusively under the tutelage of the charismatic Julian Morrow. (One small complaint: I feel I'm being told rather than shown Julian's charm and disastrous influence.)

The Secret History is a whydunit more than a whodunnit

But The Secret History is, at heart, a mystery – not so much of a whodunit but a whydunit. The novel explores the idea of how absolute ambition (social, intellectual) corrupts absolutely.

Alexandra's father compared Tartt's work with Dostoevsky, and I have to agree, if for no other reason than the novel's sweeping social and psychological scale. Each character, scene, and plot point is meticulously drawn – almost catalogued as if in a Greek drama. I don't find Tartt much of a prose stylist, but she can set a scene or fix a frame of mind for a reader without sparing even the tiniest detail. Think of it as a high-thread-count narrative. Take the following for instance:

‘I awoke from a heavy, dreamless sleep to find myself lying on Francis's couch in an uncomfortable position, and the morning sun streaming through the bank of windows at the rear. For a while I lay motionless, trying to remember where I was and how I had to come to be there; it was a pleasant sensation which abruptly soured when I recalled what had happened the night before. I sat up and rubbed the waffled pattern the sofa cushion had left on my cheek. The movement gave me a headache. I stared at the overflowing ashtray, the three-quarters-empty bottle of Famous Grouse, the game of poker solitaire laid out upon the table.'

Okay. That wasn't all that short. But it's a good novel, and I second Alexandra's recommendation.

Next week, I'll tell you what I got for Christmas…

Elizabeth Frengel is a curator of rare books at The University of Chicago Library Book Arts and History