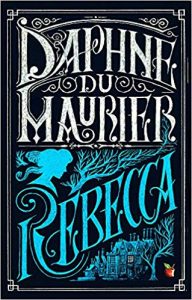

Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again. It seemed to me I stood by the iron gate leading to the drive, and for a while, I could not enter, for the way was barred to me…

You might recognize those haunting first lines from Daphne du Maurier's gothic suspense chiller, Rebecca.

Rebecca, a gothic novel…, yes

I say it's gothic, because Manderley, with its minstrel's gallery,  back passages, cordoned-off wing, echoing hall and grounds that sprawl to the sea, is just as prominent a character as the de Winters – even the creepy Mrs Danvers – in this novel, I think of as a classic retelling of Bluebeard.

back passages, cordoned-off wing, echoing hall and grounds that sprawl to the sea, is just as prominent a character as the de Winters – even the creepy Mrs Danvers – in this novel, I think of as a classic retelling of Bluebeard.

Even if you've seen the excellent Alfred Hitchcock version starring Laurence Olivier and Joan Fontaine as the de Winters and Judith Anderson as an unsettling Mrs Danvers, I promise you the book is worth a read.

What's unusual about the novel is the narrator's mesmerizing voice, whose plain recounting of her own passivity, muddled thinking and crippling shyness, I find oddly touching. Subtle repetition and du Maurier's knack for rendering interior dialogue in a way that represents natural thought give her voice a kind of poetry.

Rebecca is Maxim de Winter's first wife, dead more than a year when the narrative begins. The narrator of this tale is a lady's companion, no more than twenty-four, plucked from the protection of her dowdy patron in Monte Carlo and taken in all her ill-equipped innocence to become the mistress of the estate of Manderley, sequestered in regal glory on the Cornish coast of England.

Arrival at Manderlay

You can't help but feel the pain of her first days at Manderley, when she doesn't know which room to go to after eating her breakfast, much less what to do with herself once she's there. She thinks she hears the butler, Frith, snickering when she can't find her way to the morning room.

Worst of all she answers the first call from Mrs Danvers, the housekeeper, by saying, “I'm afraid you've made a mistake… Mrs. de Winter has been dead for over a year.” Her face then burns at the irreparable blunder. She knows she's lost her footing.

I think it's a touch of artistry that du Maurier takes such great pains to leave the narrator unnamed – always she is addressed as “you,” or “Mrs. de Winter,” or “madam.” Yet, again and again, we hear the chorus of “Rebecca” intoned throughout the novel.

Feminists will no doubt be incensed by the narrator's self-effacement and blind servility to Maxim. To give you an example: Maxim, telling the narrator he married her for her innocence, says,

‘Listen my sweet. When you were a little girl, were you ever forbidden to read certain books, and did your father put those books under lock and key?'

‘Yes,' I said.

‘Well, then. A husband is not so different from a father after all. There is a certain type of knowledge I prefer you not to have. It's better kept under lock and key. So that's that. And now eat up your peaches, and don't ask me any more questions, or I shall put you in the corner.'

Of course, Maxim has something to hide. It's Bluebeard all over again.

You wonder how the second Mrs De Winter can put up with all this. At the same time, you can't tear yourself away. And that brings us to the brilliance of Rebecca – it shows you just how easy it is to get lost in a fairy tale.

Until next time

P.S. A reader wrote in last week and rightly pointed out that not all of W. Somerset Maugham's novels (he published 84 works in total, including plays, short stories and non-fiction) begin with a bit of philosophizing and a pointed look back. Perhaps I should have said “typical of some of Maugham's novels,” or, better yet, “this novel….” That's what I get for generalizing. Mea culpa.

Elizabeth Frengel is a curator of rare books at The University of Chicago Library Book Arts and History